Two weeks ago, I climbed to the summit of the Lascar volcano in northern Chile. The 5592 m tall active volcano last erupted in October and is the most active volcano in northern Chile. Before climbing the volcano, one first has to find it. While finding the volcano itself on a map is pretty easy, information on the location of the trailhead and how to get to it proved more illusive. Most descriptions I found online contained only loose wording and none included any sort of map, which is important due to the lack of road signs in the area. I eventually found a KML file on a shady download site that contained the trail and the track to the trailhead, which was mostly correct.1 This provided enough information to find the trail, in combination with a GPS receiver.

After recording a GPS track during the climb, I added the track and trail to OpenStreetMap, so it should be easier for others to find in the future. An annotated map is below, and a KML file of the track and trail can be downloaded. To get to the trailhead, one leaves San Pedro de Atacama driving south on CH 23. Although the trip starts on paved highways, a four-wheel drive vehicle is a must for its latter parts. After passing through Toconao, one drives another 10 km south before taking a left and heading east towards Talabre on B-357. After passing Talabre, the road turns to gravel and after around 10 km descends into a valley, where the road comes to a fork. Take the right fork, fording a small stream and heading south, climbing back out of the valley.2 After continuing on this road for around 26 km, Laguna Lejía should come into view, after which one needs to take a left onto a dirt track and head north towards Lascar. The track is not always very well defined, but it wasn’t too difficult to follow.3 Lascar is in view at this point, so one essentially just needs to drive towards the smoldering volcano. The “parking” area for the trail is after about 14 km; it’s an unmarked area on the slope where the track turns into a trail that is essentially as far up as one can drive before the grade becomes too steep for a vehicle. It is important to note that as one gets close to the trailhead, the ground becomes covered with a layer of loose aggregate, which is easy to become stuck in if one drives off the track.4 The ~110 km drive from San Pedro de Atacama took around two and a half hours.

Here, at around 4930 m, the climb begins. Although it should go without saying, climbing an active volcano, and climbing at altitude in general, can be dangerous, and you should do so at your own risk; in particular, one should check for recent volcanic activity. There is an easily discernible trail the entire way up, although in sections it splits into switchbacks for the way up and a straight route for the way down. Much of the trail surface is composed of loose volcanic soil, which making hiking a bit more difficult; the climb is decently steep, averaging 24% grade. Also, due to the altitude, there is around half the oxygen there is at sea level. A winter coat and boots were a necessity. An elevation profile derived from my GPS track is below. It is around 2.3 km to the crater rim with ~560 m of vertical gain; it is then another ~0.6 km to the summit with ~110 m of vertical gain. It took my climbing partners and I around three hours to ascend and one hour to descend; we also spent around half an hour at the top, split between the summit and crater rim, to take in the view and have lunch. We were fairly well acclimatized, having spent the previous two weeks staying in San Pedro de Atacama at ~2400 m and working almost every day at ~5200 m, although none of us climb mountains on any sort of regular basis. I started the hike with just under 5 L of water and drank around two-thirds of it before returning to the truck. Between the vertical gain and lack of oxygen, I certainly felt the weight of the water (and an emergency oxygen bottle).

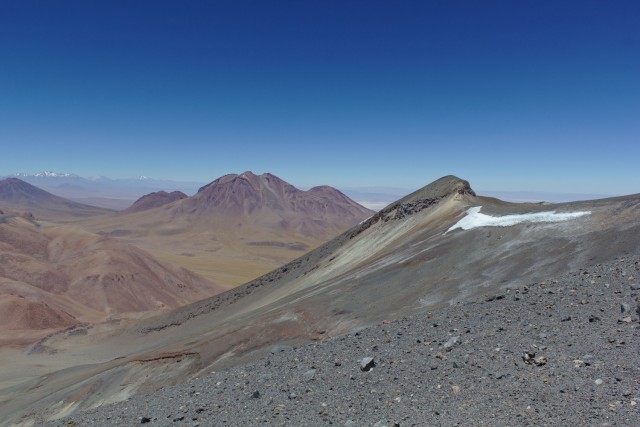

Looking down into the crater, one sees plumes of volcanic gases, a testament to Lascar being an active volcano. Fortunately, the gases were not being blown towards the trail on the day I climbed, although one could certainly still smell the sulfur. The view from the summit is breathtaking; the barren volcanic landscape barely seems terrestrial. One can see dozens of other volcanoes in all directions. The summit is marked by a stone cairn (and volcanic monitoring equipment). It is also extremely windy at both the crater rim and the summit, to the extent that it was difficult to stand upright. Fortunately, rock wind shelters have been built at both locations, which provide respite; at the summit one can sit and rest in the lee of the shelter while taking in the view to the south. On the climb up, my climbing partners and I passed two groups of climbers on their way down—both groups appeared to be guide-led; on the way down, we passed a pair of Chileans on their way up. Once we got back to our truck, we ran into a group of volcanologists who were there to collect gas samples from within the crater; Lascar was just one stop on their expedition to many volcanoes in the area. Not only were they climbing the volcano, but they were going to carry lots of equipment with them and climb down into the crater. Although we did see other people while hiking, we didn’t pass a single vehicle between leaving and returning to the main highway, CH 23, west of Talabre while driving (it was a Sunday).

Either on the way to or from the volcano, one should also definitely stop at Laguna Lejía, the salt lake at the turn off from the road.

More photos are in an album on Flickr.

Hi Matthew, I’ve just stumbled across your “private” tour on Lascar volcano. We’ll be staying in the Atacama desert for a bit more than one week in March 2018. Lascar is on our list, but we don’t like guided tours :-(. I may have a couple of stupid questions. One of them is: Could I get in touch with you directly via email? Thanks, Rainer (from Germany)

You can find a contact email address on the about page.

Kia ora Matthew, great piece here, really informative. I too have a stupid question; just wondering what your thoughts are on carrying emergency oxygen on this trail, as I note you took a bottle of it? Is this necessary, and if so where might one source this in San Pedro/Calama? (or would one have to pick some up in Santiago and travel with it?) Many thanks!

There’s currently a 5 km exclusion zone around the crater due to an increased risk of eruption, so hiking the volcano right now would not be a good idea. Carrying oxygen is not really necessary but is an additional safety precaution. Oxygen cylinders can be refilled in Calama at Linde, but I don’t know where you can rent one (I work on a telescope on one of the mountains in the area, so we have oxygen on hand).

Thanks for your help, wouldn’t have seen that otherwise! Much appreciated. We’ll be arriving in early September so I’ll check that page again to see if the exclusion zone’s still in place (I assume this is the best website to check?). Cheers mate

Pingback: Climbing Cerro Zapaleri | Matthew Petroff