Early Monday morning, my brother and I drove north from the Boston area to Maine for the total solar eclipse. Originally, we had planned to view the eclipse from New York, in the Adirondacks, but, a few days prior, the cloud forecast for Maine was looking much better.1 The goal in either case was to climb above the tree line for the eclipse, and with clouds in the forecast for New York, the Vermont peaks being closed for mud season, and the New Hampshire high peaks being too far south, that left Maine. We considered both Mt. Abraham and Mt. Bigelow, before deciding on Mt. Bigelow for its easier access and longer period of totality.

Leaving around 4 am, we encountered no traffic until shortly before reaching our destination, the Bigelow Preserve, where we were stuck in stop-and-go traffic for 15–20 minutes; the traffic was trying to turn into the access road for the Sugarloaf ski resort, which was backed up. Due to a lack of winter road maintenance on Stratton Brook Pond Road, we parked on ME-27, where the Appalachian Trail crosses it; as it was a busy day on the trail, the parking lot was full, and we parked on the side of the road. We started hiking shortly after 9 am carrying our snowshoes but quickly decided to put them on. There appeared to be at least a foot of snow on the ground, and the trail was a bit icy at this point, with a satisfying crunching noise while walking, although the snow became much softer as the day went on and temperatures rose well above freezing. When the Appalachian Trail started to climb the mountain, which was quite steep at times, the several layers we were wearing became much too warm, and we both stripped down to just a t-shirt for the remainder of the climb.

As we gained elevation, the snowpack increased, to the point it was burying—or almost burying—the trail blazes at times. While the path others had taken before us was easy to follow, it wasn’t always actually on the trail, due to the difficult-to-find blazes, so we broke new trail in the snow in a few spots to return to the actual trail. Even when we were on the trail, it often involved pushing through fir branches—dripping with melting snow—since the snow was so deep such that we were above the region clear of branches. Once we reached the small, unnamed peak just east of The Horns Pond, we were rewarded with our first scenic viewpoint.

From here, it was downhill to the pond, before more uphill to South Peak, one half of The Horns. Next, there was significant downhill before the final climb to West Peak, where we broke out above the tree line and reached the summit around an hour before totality and around five and half hours after starting the hike.

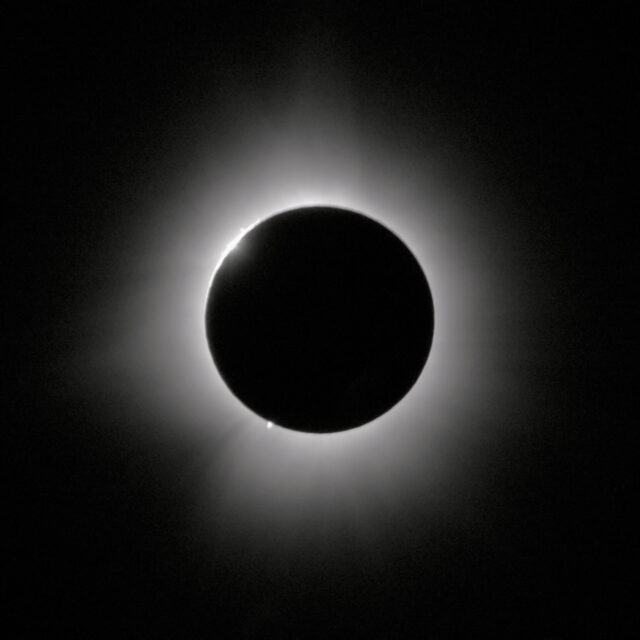

At the summit, there was a brisk wind, so we quickly put on several layers, including winter coats, before eating lunch. There were also two to three dozen people at West Peak for the eclipse, and we could see more to the east on Avery Peak; some of these folks seemed rather ill equipped for the conditions, without snowshoes or even crampons (and there was one guy wearing sneakers). We decided to backtrack downhill slightly east and head south of the ridgeline to avoid the crowds and get in the lee of the ridgeline. Here, we began to set up our gear, which involved cutting out and compacting a ledge in the steep, snow-covered slope. As with the last eclipse, I used a 70-300mm telephoto lens at 300mm with a 2x teleconverter (and a 3D-printed solar filter holder) on a 1.6x-crop-factor camera (although a newer camera than last time) and also used my Ricoh Theta Z1 panoramic camera (instead of my Theta S like last time). Instead of bringing a full tripod, I brought just the head from my tripod and a small makeshift tripod I made the day before out of three 18″-long, 1″-square, birch dowels and a 3D-printed plastic junction. This was much lighter and fit inside my day pack, along with a monopod for the panoramic camera, which I jammed into the snow, but it was still a very-heavy day pack between all of the camera equipment, water, extra layers, etc. The setup process was a bit rushed, and I only finished a few minutes before totality began. Thus, I didn’t have time to carefully focus my lens on sunspots and had to rely on autofocus, which ended up being slightly off (and my brother was also slightly off on the focus of the telescope he brought).

The trip and climb were well worth it. Not only were there perfect skies and amazing scenery, but you could see the moon’s shadow approach and then leave over the landscape, and there was a great view of the horizon and the sunset-like sky above it.

Afterward, we sat around and watched the sun for a bit before packing everything up and starting to head down, around an hour after totality. We were the last to leave, besides a couple and their dog. Instead of going down the way we came, we took the steeper and more direct—and thus shorter—blue-blazed Fire Warden’s Trail. In particular, this trail did not go over any other peaks, so it was all downhill until the base of the mountain, after which there were some rolling hills and an uphill to reach the road and the parked car; this was important, as I was rather sore at this point, particularly with the heavy day pack and the unusual gait required with the snowshoes. After passing four or five people on the trail, we became stuck behind a dozen or so (what I assume were) undergrads in some sort of organized group—some of whom were rather timid about the steep downhill on soft snow and thus pretty much stopped; after they let us pass, we were able to make reasonably-fast progress the rest of the way down the mountain, although I was sore and thus slow on the uphill sections after that (and was definitely slowing my brother down). We made it back to the car at dusk, around 8 pm, roughly three and a half hours after leaving the summit and eleven hours after beginning the hike.2 In total, the hike was 14–15 miles long, with several thousand feet of elevation gain.

After the hike, we stopped at Sugarloaf for my brother to go for his daily run, where there was bumper-to-bumper traffic leaving; clearly, Sugarloaf held some sort of event after the eclipse, since it was dark, and they don’t have night skiing. When we left Sugarloaf, the traffic was gone, although we eventually caught up to it. Once we stopped for dinner, that traffic was also gone, and we encountered no other traffic on the return trip, for what ended up being a very long day trip.

I was carefully checking both the ECMWF cloud forecast online and loading the NWS National Blend of Models into QGIS, with roads, borders, and the region of totality overlaid. ↩

The folks we passed on the way down clearly did not make it back before dark (although the undergrad group looked like they might have been planning on camping), and there were still several cars parked along the road when we left. ↩