Last month, I climbed Cerro Zapaleri, the 5648 m tall summit of which forms the tripoint of the borders of Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia.1 Its location is quite remote, ~105 km from San Pedro de Atacama, Chile and >40 km from the nearest paved road, both as the crow flies. After researching previous accounts of ascents and poring over high-resolution satellite imagery to map out routes to get to the mountain and to climb it, it was time to depart. As expected, a high-clearance four-wheel drive vehicle would prove to be necessary.

A colleague of mine working on the CLASS project and I left our accommodations in San Pedro de Atacama shortly after 5 am2 and met up with some associates from the ACT project, in a second four-wheel drive pickup truck, at the start of the Jama road (CH 27) at around 5:30 am. As with previous climbs of Lascar and Cerro Toco, we informed others of our plans and took a satellite phone and satellite-based locator beacon as precautions. We then proceeded to drive toward the Argentinean border, to kilometer 147.5,3 arriving just before 7 am. We then turned off the Jama road and began following a dirt track north after crossing the buried gas pipeline. As it was still dark, finding the turn-off was somewhat challenging, although once we found it, following the dirt track was not too difficult (but a bit bumpy). We stopped to watch part of the sunrise over Laguna Helada.

As we continued to drive north, we crossed two washes. The first had some water, but the second was dry; neither presented any challenge to cross. Shortly after 8 am, we reached Río Zapaleri, at a location just upriver from where the Quebrada de Chicaliri tributary joins. While tracing out the route to the mountain on the satellite imagery, I was concerned that we would not be able to ford the river here. No accounts of previous ascents involve taking this route. Most cross the river at the Argentinean border and climb via the gulch just over the border4 or ford the river on foot and climb by a similar route. The tracks visible in the satellite imagery showed that the standard route was considerably better traveled, crossing the border at “Paso Zapaleri.” However, this would result in a significantly longer climb, which I sought to avoid. Fortunately, we were able to ford the river at the Quebrada de Chicaliri confluence without difficulty, although our pickup truck’s high clearance proved essential in doing so. This year, February and March were drier than normal, and our March 16 climb was a week after the last time it had snowed on Zapaleri (per Planet Labs satellite imagery); if it had been wetter, we might not have been able to cross.

We then drove out of the ravine5 and continued north toward the Bolivian border. Around 2.5 km from the Bolivian border, we turned off the established track6 toward the northeast and began following the bottom of a ravine in the direction of the Zapaleri summit. We continued up this ravine until the combination of the steep slope and the high altitude meant that we did not have sufficient engine power to go farther, even in 4L, and then parked the trucks perpendicular to the slope shortly before 9 am. My prediction for the trailhead based on the satellite imagery and digital elevation models proved to be quite accurate; GPS coordinates put the location where we parked only ~20 m from the location that I had marked on the map before setting out.

As Zapaleri is rarely climbed, and even more rarely climbed via the route I planned out, there was no trail. We began our climb by heading east, to the top of one of the ridges that border the ravine we drove up.7 We then followed this ridge to the northeast until it met a larger ridge. We continued climbing to the northwest along the larger ridge to near the summit. In retrospect, the climb would have been easier if we had climbed parallel to the ridge but slightly downhill from it toward the northeast. This would have avoided climbing over some of the outcroppings that are along the ridge and kept us out of the wind. However, the climb along the ridge provided an outstanding view toward the southwest, which we would have missed if we had stayed out of the wind.

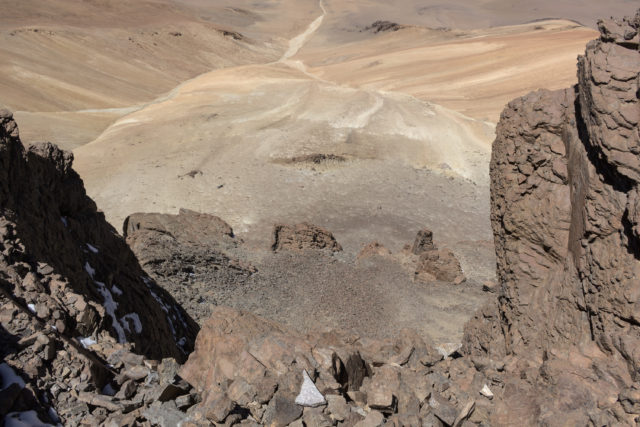

Next, we turned toward the northeast and headed for the summit. The final summit is quite impressive and abruptly sticks up from the rest of the mountain.8 The only non-technical route up it is from the west, and this involves a scramble up an extremely steep slope comprised of loose rock and scree. If we had known this in advance, my colleague and I would have brought climbing helmets, which I would recommend for safety. We climbed the slope while following the base of the cliff face, since this gave additional hand-holds. We climbed one at a time and stopped at regular intervals in areas of more secure footing to allow each other to catch up, since this reduced the risk of being hit by rocks that were knocked loose.

Finally, we reached the summit at ~1:15 pm. The summit contains a three-sided painted steel border monument and is surrounded by steep drop-offs. The view is incredible. Additionally, if one walks north of the border monument, the bright green crater lake is visible.9 Although the mountain is not climbed particularly often, we did find a note left by recent climbers in a small, empty liquor bottle; apparently, a group of Argentinian narcotrafficking police officers climbed on 24 December 2020.

Using the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission 1-arcsecond (~30 m) digital elevation model (DEM), I calculated an elevation profile for the climb. According to these data, the approximately 2.4 km climb had ~630 m of vertical gain, resulting in an average grade of ~26%; the maximum grade was ~48%. However, the DEM does not have the resolution necessary to resolve the summit features, and the final push to the summit was almost certainly even steeper. Additionally, the DEM seems to systematically underestimate the elevation, at least when compared to the GPS track I recorded (which put the summit elevation at ~5700 m).

After around an hour at the summit, we began to head back down. While my colleague from CLASS had made it to the summit with me, our associates, some of whom were not as well acclimatized, did not, although some came close. We climbed slower than we would have otherwise and waited at the summit for them to catch up, but with the wind and the cold, waiting around while not moving is not particularly pleasant, and we eventually gave up and departed. The way down from the summit proved to be the most difficult part of the climb. Due to the steep slope and loose rocks and scree, it involved mostly sliding down on one’s derriere and using one’s feet and hands to try to not slide too much and to not knock loose too many rocks. Once down from the summit, the rest of the climb down was not too bad, although the steep slope again made progress somewhat slow. We stayed downhill from the ridge we had climbed up on, to stay out of the wind. We made it back to the trucks at around 4 pm, seven hours after we had started climbing. I ended up going through around half of the ~3.5 L of water that I had carried. After a brief rest, we began driving back to San Pedro de Atacama. Driving both to and back from Zapaleri, we saw many, many herds of vicuñas,10 and on the way back, we also saw a half dozen puna tinamous. We made it back to the paved Jama road at ~5:30 pm and back to San Pedro de Atacama at ~7:15 pm, roughly 14 hours after we had left.

After returning to the United States, I did some research on the origin of the summit border monument to try to determine when it was installed. The best resource I could find on this was a 1953 report on marking the border between Argentina and Bolivia (which is also where the 5648 m elevation I used in the first sentence of this blog post came from).11 In addition to a written description of the border and survey, the report contains detailed maps, photos, and drawings of the border monuments.

Although the border between Chile and Argentina was surveyed and marked around 1900, the summit of Cerro Zapaleri was neither surveyed nor marked at that time.12 However, the Argentina–Bolivia survey, which started in 1939, did mark it on 30 November 1940.

If one compares the photo and drawing of this original border monument to the photos of the current one earlier in this blog post, it is readily apparent that the current one is much shorter than the original 3.5 m tall monument, approximately half the height. A closer inspection of the cross-bracing reveals that the monument was not just shortened but that it was completely replaced; the cross-bracing on the current monument is installed on the outside of the angle irons instead of on the inside,13 and the bracing on the current monument connects to the angle irons farther from the top of the monument than on the original. Unfortunately, I was unable to determine when or why the monument was replaced. However, graffiti on the current monument mentions years dating back to 1997, so the monument was clearly replaced sometime before then. In addition to the monument, I located three brass survey markers. The Bolivian Instituto Geográfico Militar installed a triangulation station marker and an associated reference marker in 1965, and the Chilean Instituto Geográfico Militar installed a triangulation station marker in 1970.14 I was unable to locate any documentation on these markers, so I can’t say whether or not the replacement of the border monument was associated with the survey marker installations.

This was at the end of a nine-week trip to Chile for telescope repair and maintenance work. Traveling during the COVID-19 pandemic, even with an N95 mask and PCR tests, was a nightmare, particularly for the flights in the United States, and I would not have done so if the repair work wasn’t necessary. ↩

This was the earliest we could leave, since the COVID-related curfew ended at 5 am. However, leaving earlier would have involved more driving off-road in the dark, which is less than ideal. ↩

An alternative turn-off at kilometer 144.4 can also be used. ↩

This is consistent with what was communicated to me via my colleagues from the local tour guides they know. ↩

The track was extremely rutted on the steep slope, and I would highly recommend using 4L for this to avoid having to maintain higher speeds to maintain engine power. ↩

Per satellite imagery, the track continues on and crosses the Bolivian border. ↩

Heading directly toward the summit would have been a much steeper and more difficult route. ↩

I attempted to use photogrammetry to reconstruct a 3D model of the summit using drone footage from a Chilean TV show. Unfortunately, the low-quality video frames combined with a lack of orbiting shots led to a failed reconstruction. I didn’t bring my DJI Mavic Mini to take my own photos for photogrammetry, since it can’t handle the high altitude (it barely flies at ~5200 m without any wind). ↩

We considered stopping at the lake on the way down but decided against it, since it would have involved an additional uphill climb to return from it. ↩

These vicuñas were far more skittish than the vicuñas found along the Jama road or on Cerro Toco. ↩

Informe Final De La Comision Mixta Demarcadora De Limites Argentina–Bolivia. Buenos Aires: Talleres Gráficos del Instituto Geográfico Militar, 1953. ↩

La Frontera Argentino–Chilena: Demarcación General, 1894–1906. Buenos Aires: Talleres Gráficos de la Penitenciaria Nacional, 1908. ↩

A detailed photo of a different monument in the same publication shows that the actual monuments matched the drawing. ↩

I did not find any markers from Argentina. ↩